CRISPR is a recently discovered genomic tool that could potentially revolutionize genetic modification and editing, including gene silencing, editing, activating, and other crucial functions. It has made a big splash in the synthetic biology community, and mentions of CRISPR have started cropping up elsewhere in the biotech world – many companies have already sprung up, hoping to quickly commercialize the CRISPR gene editing technologies.

As a result, you may have heard of CRISPR, even if you aren’t deeply immersed in the microbiology and synthetic biology literature. This guide is an attempt at explaining the basics of the CRISPR technology to someone with only a passing knowledge of modern microbiology. Although I include some review, I expect you to have a good understanding of what DNA, RNA, and proteins are, and how the processes of transcription and translation link them all together.

Microbiology Review

Before we dive into CRISPR, let’s go over the basic building blocks of microbiology: DNA, RNA (of various types), proteins, and the processes of transcription and translation.

Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic DNA

All living things store their genetic code in a molecule called deoxyribose nucleic acid, or DNA for short. Different types of organisms will have different numbers of DNA molecules, sometimes of different shapes. Eukaryotic organisms (roughly speaking, plants, animals, fungi, and so on) will have their DNA molecules in bundles called chromosomes. Eukaryotic organisms will often have many chromosomes – humans usually have 46 chromosomes in each cell.

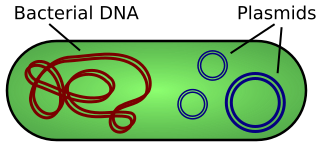

Prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria only have a single chromosome, and, unlike eukaryotic chromosomes, bacterial chromosomes form a loop. Bacteria also have small circular bits of DNA called "plasmids" floating around in the cell.

Each chromosome or plasmid really is a single very long molecule. Each molecule has a backbone composed of deoxyribose sugars linked by phosphates. Along this backbone lie nucleotides, which in DNA are adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine, or A, T, G, C for short. Just like computers use a binary code, so does DNA use a quaternary code to represent genetic information which can be used by the organism in various ways. DNA is a double stranded molecule, which means there are two of these backbones linked together. They are linked by hydrogen bonds between nucleotides: adenine bonds with thymine and guanine bonds with cytosine, meaning that As are always opposite Ts and Cs are always opposite Gs.

mRNA and Transcription

Most reactions that drive the day to day life of cells are done by molecules called proteins. There are thousands and thousands of different proteins with incredibly varied roles, and cells are constantly making new proteins and changing the proteins they are making in reaction to outside events. All of the information describing how to construct various proteins lies encoded in the DNA of an organism, but before the proteins are made, the information goes through another phase called transcription.

During transcription, a protein called RNA Polymerase attaches to the DNA. It slides along the DNA creates a copy of it; instead of using a deoxyribose sugar in the backbone of the molecule, it uses a sugar called ribose, and so the molecule is called RNA (ribonucleic acid). The two main differences between RNA and DNA are that RNA is usually single-stranded (no complementary RNA hanging around) and RNA uses a uracil (U) instead of thymine (T), so replace all Ts with Us.

When RNAs created by RNA Polymerase are meant for eventual conversion into proteins, they are called messenger RNAs, or mRNAs, because they can float away from the DNA and act as a messenger to ribosomes, the protein-producing factories of the cell. However, not all RNA is mRNA – RNA has other uses besides being turned into a protein by ribosomes.

Proteins and Translation

The final step in the process of producing proteins is known as translation. During translation, a messenger RNA will be brought to a ribosome. The ribosome will attach to a portion of the mRNA known as the ribosome binding site (RBS), and, like the polymerase did, will start sliding along the mRNA. The ribosome slides along in groups of three called "codons". As it slides, it will build a protein molecule out of smaller chunks called amino acids. Each codon corresponds to a particular amino acid to add to the growing molecule; for example, the sequence CGG corresponds to the argenine (Arg) amino acid. In fact, there’s even a table that explains how these three-base codons correspond to the twenty amino acids.

To recap, DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) is an information-containing molecule made of a sugar-phosphate backbone with information encoded as a sequence of nucleobases usually called A, C, G, and T. DNA is commonly (but not always) double stranded, with the two strands sticking together through hydrogen bonds between the bases, with A bonding to T and C bonding to G. DNA gets transcribed into RNA (ribonucleic acid), which is like DNA but uses a different sugar and usually single-stranded. RNA comes in different types, and the type that gets transcribed from DNA with the eventual goal of being translated into a protein is called mRNA (messenger RNA). Ribosomes are complex cellular organelles which latch onto mRNA at ribosome binding sites and translate the RNA into proteins through a process called translation, with each triplet of bases (called codons) corresponding to one amino acid incorporated into the protein.

What is CRISPR?

Loosely speaking, CRISPR is a set of tools for genomic editing and modification. Although scientists are beginning to put CRISPR to their own purposes, it wasn’t invented by scientists, but rather was discovered: it is a naturally occurring very basic immune system in bacteria which scientists have learned to replicate and use for their own purposes.

Discovery of CRISPR

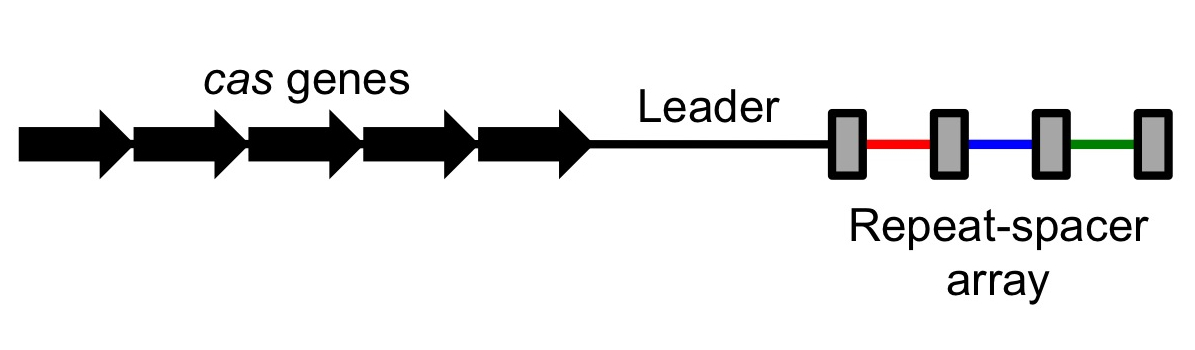

Scientists observed that many bacterial genomes had a strange pattern to them. In some places, sequences of unique DNA (roughly 20 base pairs) would be separated by shorter repeats. This area would form an array of unique sequences separated by regularly interspaced short repeats; scientists also observed that these repeats had a tendency to be somewhat palindromic (read left to right or right to left, they yielded a similar sequence of letters). There regions were dubbed CRISPR, standing for "Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats".

These regions were non-coding – that is, unlike coding DNA, which gets transcribed and eventually translated into proteins, these regions were transcribed but never translated. They did not end up as proteins. However, next to these CRISPR regions there would always be a few coding sequences (sequences that were eventually turned into proteins), and these sequences were roughly conserved over different types of organisms.[1] In other words, sets of very similar genes and correspondingly similar proteins were associated with CRISPR; these were dubbed CRISPR-associated sequences (Cas) with corresponding Cas proteins. As different Cas proteins were discovered, they were numbered, leading to Cas1, Cas2, and so on, with one of the most commonly used proteins being Cas9.

It took over two decades for biologists to figure out what these CRISPR regions and Cas proteins were for (and some biologists think that we still aren’t done discovering their many uses). This CRISPR/Cas system, as it turns out, is a very simple adaptive immune system for bacteria and other prokaryotes. Bacteria are regularly invaded by viruses, which are small bits of protein and foreign DNA bundled together. Viruses inject their DNA into the bacterium and then use the bacteria’s DNA replication capabilities to make more copies of themselves, usually with harmful results to the bacterial cell.

The breakthrough came when a team of scientists observed that the unique sequences in the CRISPR regions weren’t just random, but that many of them came from viral DNA. For some reason, bacteria incorporated small chunks of DNA from viruses into these sequence clusters, separated by short repeats. It was already known that some of the Cas proteins (CRISPR-associated proteins) had the function of nucleases, which are proteins that can cut or break DNA or RNA. Upon discovering that CRISPR held viral DNA, everything clicked! The Cas proteins were weapons, designed to destroy invading viruses.[2] But in order to attach the right DNA, these antiviral weapons had to be targeted, and the CRISPR region was a DNA targeting system. Together, the CRISPR/Cas system was a simple immune system: the non-coding DNA would target the invading viral DNA, and the Cas proteins would follow where the CRISPR sequences pointed and cut up that invading DNA in order to destroy the virus.

CRISPR/Cas Overview

At this point, let’s recap what we know about the CRISPR/Cas system and at the same time go into a little bit more technical depth.

CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats and Cas stands for CRISPR-associated sequence. These two regions tend to be very close together on the genome. As a result, when the CRISPR/Cas regions are transcribed (copied by an RNA polymerase from DNA into RNA), they are transcribed in tandem. If CRISPR is expressed, so is Cas, allowing them to work together.

The Cas proteins have different functions. Some of them, like Cas9, are nucleases – proteins which attach to DNA and cleave it (either both strands or only one strand). Some, like Cas1, have a slightly more complex purpose: they take invading viral DNA and incorporate it into the CRISPR region. By constantly incorporating new viral DNA into their CRISPR regions, bacterial cells effectively learn about their enemies, so that the next time the virus shows up in the bacterial cell, the CRISPR/Cas system can quickly target and destroy it.

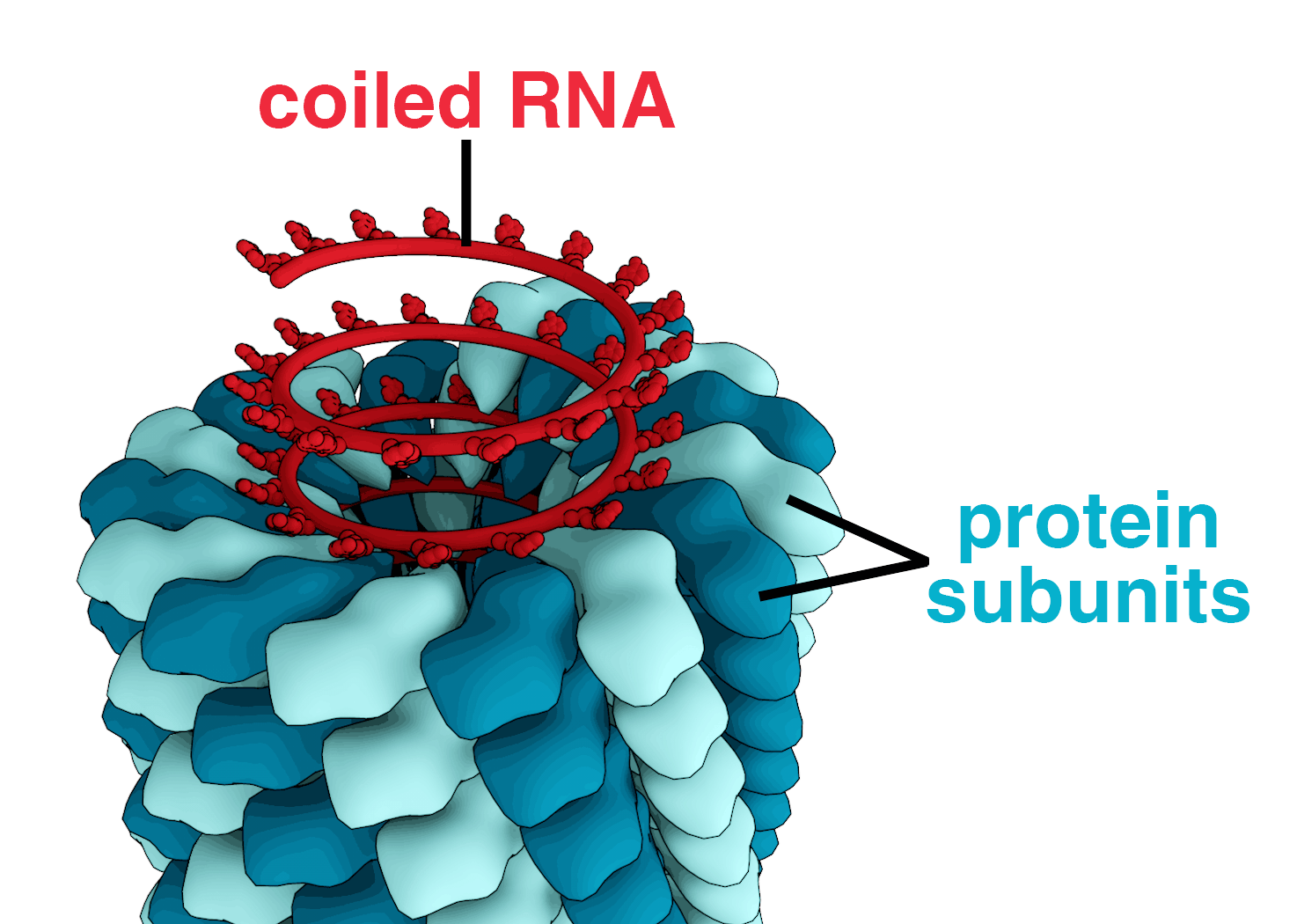

Several steps have to happen in order for the CRISPR/Cas system to target and destroy a virus. First of all, the nuclease Cas protein must be transcribed into RNA and then translated by ribosomes into a full protein. At the same time, the CRISPR region must be transcribed into RNA; this transcript is a long chunk of RNA known as the CRISPR RNA. After some processing, the CRISPR RNA is cut into smaller chunks called crRNAs (a creative shorthand for "CRISPR RNA"), with each cut being on one of the palindromic repeats; each crRNA transcript consists of one of the spacers (the chunks of viral DNA), followed by some auxiliary RNA. Once the crRNA and Cas proteins are ready, the Cas protein binds tightly to the auxiliary bits of the crRNA, forming a protein-RNA complex. Although the DNA is bound to the protein, the viral DNA spacer is still accessible from the ouside world, so it can bind to other DNA while also bound to the protein. [3]

At this point, the crRNA-Cas complex is ready to cleave viral DNA. Recall that DNA forms double-stranded compounds due to hydrogen bonding between the bases (in DNA, A binds to T and C binds to G, and in RNA, the T is replaced by a U). Since the backbones of the molecules do not interact at all, not only can DNA strands bind to other DNA strands, but RNA can also bind to DNA. This is exactly what happens: the crRNA binds via interbase hydrogen bonds to freely floating viral DNA. However, since these hydrogen bonds can only happen on complementary strands, the crRNA can only bind to the virus from which it originally came. In this way, the viral DNA spacer guides the Cas protein specifically to the virus DNA. Since this spacer is fairly long (20 or so nucleotides), it can be fairly unique in the genome, which means that the crRNA targets exactly the viral DNA and nothing else, making mistakes only very rarely. Once the crRNA-Cas complex attaches via these hydrogen bonds to the viral DNA, the Cas protein cleaves both strands of the viral DNA, destroying the virus.

CRISPR as a Tool

Although CRISPR seems to have evolved in bacteria as an adaptive immune mechanism, the CRISPR/Cas system is much more generic and powerful than just a virus-destroying mechanism. With only minor changes to the sequences and proteins, we can use CRISPR/Cas as a method of gene editing. Although scientists are still exploring the full applications of this system to DNA modification, many applications have already been demonstrated.

Controlling Cas Targeting

Scientists have long known how to insert DNA into cells. For example, many bacterial cells (so called "competent" cells) will naturally accept plasmids from their environment. As mentioned earlier, plasmids are small rings of DNA that compose some of the bacterial genome (separate from their main circular chromosome). Competent bacteria will accept plasmids from their environment, at which point their RNA polymerases will transcribe them, and they are treated like standard DNA. Thus scientists can design sequences containing the CRISPR repeats and Cas genes, put them in plasmids, and add those plasmids to bacteria, and some bacteria will naturally accept the plasmids, allowing them to exist within the cell and be treated as if they were part of the bacterial genome.

Since we know how to add DNA to a cell, we can easily control the CRISPR/Cas targeting mechanism. We can create a plasmid that contains the Cas genes and the CRISPR sequences, with the spacers containing a sequence complementary to whatever location we’d like to target.[4] Once that plasmid is incorporated by a competent bacterium, the CRISPR sequence will be transcribed, thus activating the custom-targeted CRISPR/Cas system. Scientists have figured out how to quickly and efficiently create these guiding spacers, making it very easy to target specific locations; in fact, it is even possible to target many locations at once, with recent studies demonstrating targeting of up to five locations.[5]

Silencing and Activating Genes

The way cells behave is highly dependent on which genes are active at any given time. Cells constantly change which genes are active in order to respond to external stimuli and stressors; for example, many bacteria can survive under very diverse environmental conditions, and react to changes in their environmental conditions by regulating which genes are being expressed. The expression of a gene is regulated by the frequency of transcription and translation of that gene; if the gene is rarely transcribed, then it is never turned into a protein, and thus does not affect the behaviour of the cell; if a gene is very often transcribed, the generated protein can strongly dictate the behaviour of the cell.

There are many, many ways to regulate gene expression, ranging from incredibly simple to enormously complex systems. Not only can genes be just "on" or "off", but they can also be part of complex positive and negative feedback loops, with the expression of many genes being intertwined into one complex regulatory system.

Since gene expression plays such a large role in cellular behaviour, ideally we’d like to control it; as it turns out, the CRISPR/Cas system offers us several ways to do so!

Silencing a gene with CRISPR/Cas is incredibly simple. The Cas protein has two active sites; one active site cuts one strand of the DNA, and the other active site cuts the other strand. Through studying the Cas9 sequence and protein, scientists know which part of the sequence corresponds to which active site, and so have been able to modify the sequences to break those active sites (so that they are no longer effective and cannot cleave the DNA strands), yielding a protein called dCas9 (with the "d" standing for "dead"). Although dCas9 cannot cleave the DNA, it still retains its targeting functionality. Thus, the dCas9 targets the location the gRNA guides it to, but instead of cleaving the RNA, it just sits there, doing nothing. However, since there’s a dCas9 firmly bound to the DNA, RNA polymerases cannot attach to and transcribe that DNA! Since RNA polymerases cannot access the gene (dCas9 is in the way), it has been completely silenced.

The core idea behind activating a gene is similar (although the implementation is somewhat more complex). In order to activate a gene, instead of using a catalytically dead dCas9, we would use a protein complex known as CRISPR/Cas9 SAM (Synergistic Activation Mediator). Instead of being inactive, the SAM complex can be created in various ways in order to attract polymerases and other necessary proteins to the DNA, causing an increase in transcription. We then design the guide RNAs to place the CRISPR/Cas SAM complex upstream of the gene we actually want to express (in order to avoid blocking the actual desired sequence). Thus, in addition to silencing a gene by removing the cells ability to transcribe it, we can also activate it and increase its rate of transcription.

Breaking Genes

In addition to silencing and activating genes, we can use the CRISPR/Cas9 system for what it does best: destroying DNA.

Suppose we have a protein that we’d like to knock out or make ineffective, so that it no longer affects that cell. As before, we start by designing a proper gRNA to target the Cas9 to the coding sequence for the protein. Using a standard Cas9, we let the Cas9 create a double-stranded break (DSB) in the target DNA.

When this happens to viral DNA, the DNA is completely destroyed and the virus is killed. However, when this happens to bacterial or eukaryotic DNA, that’s not quite the end of the story. Both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells have DNA repair mechanisms that attempt to fix issues with damaged DNA in an attempt to prevent the cell from dying or becoming cancerous.

One such repair mechanism is known as non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). NHEJ is an emergency measure – a last resort to avoid cell death. During NHEJ, several proteins act together to stitch together the broken ends of the DNA. However, the repair enzymes act somewhat chaotically: they do not have a defined order, can act multiple times until the breaks are fixed, and function independently of one another. As a result, the joining is often highly error prone, inserting a few bases or deleting a few bases into the sequence. Although there is a chance that the joining will correct the break perfectly, in that case, the CRISPR/Cas complex will just cut it again, continuing the process until the joining fails to correct the break.

At best, this will insert or remove an amino acid into the resulting protein sequence, if exactly three bases are inserted or removed. More commonly, however, there will be one or two inserted or deleted bases, causing a frame shift mutation. A frame shift mutation occurs when a mutation changes the number of bases by one or two (or any value that isn’t a multiple of three). Since proteins are translated in triplets, being off by one or two bases shifts the entire rest of the protein, almost always making it entirely non-functional.

Thus, we can usually easily break any gene we can target, simply by letting Cas9 play out its standard nuclease role and allowing NHEJ to introduce errors into the DNA during DNA repair.

Replacing Genes with Custom Sequences

We’ve discussed breaking, silencing, and activating genes, and now it’s time to finish up this guide with the grand finale of gene editing: replacing parts of a genome with a completely custom designed sequence. Although we’ve been able to do that via other means before, the CRISPR/Cas system makes this much simpler and much more reliable.

The key to inserting custom sequences once more lies with cells' natural DNA repair mechanisms. In addition to the error-prone NHEJ, many cells have another DNA repair mechanism, known as homology-directed repair (HDR). Unlike NHEJ, HDR relies on the presence of a homologous piece of DNA floating around in the cell; that is, a piece of DNA that is very similar to the DNA being repaired. Homology-directed repair is much more reliable than NHEJ, since many homologues are indeed identical, and so copying a homologue is a pretty good strategy for repairing a broken piece of DNA. This repair mechanism exists mostly in cells which have multiple copies of their chromosomes; this includes plant and animal cells but not bacterial cells, so most bacteria do not have an HDR mechanism.

We can induce DNA repair mechanisms by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to break the target DNA.[6] If no homologues exist, then NHEJ happens, usually breaking the gene. However, we can induce HDR by adding large quantities of homologous DNA to the cell; then, instead of breaking the gene, the cell will copy the homologous DNA into its genome in an attempt to repair the DNA breaks.

Most importantly, the cell does not care about the entire content of the homologue, but rather only about the ends. The ends of the homologue must match up very well with either side of the DNA break, so that the homologue can bond to the broken DNA and then be copied during the repair. Since the middle of the homologue is unimportant, we can put whatever DNA we want in it, thus replacing any target gene with our own custom-designed sequence!

Conclusion

In this guide, we briefly went over the basics of genetics in a quick microbiology recap. We then went over the history of CRISPR, how it was discovered, and what use it has in bacterial cells. Finally, we looked at how scientists can control the CRISPR/Cas mechanism for their own purposes of genetic editing and modification.

The first uses of the CRISPR/Cas system were only a few years ago, around 2011 to 2012. This tool has been incredibly promising, and so research into it and its applications has been flourishing, with some expecting over a thousand papers relating to it around 2015-2016. (Unfortunately, it seems like there is some debate over who invented CRISPR and should be awarded the patent for it.)

Multiple companies have already formed around CRISPR, hoping to commercialize the technology for purposes ranging from general gene editing techniques to targeted therapeutics. The technology has been used to edit everything from bacterial cells to C. elegans nematodes to zebrafish and even human cells; one group is even aiming to use it to insert woolly mammoth genes into modern elephants to revive the mammoth! The applications and variations on CRISPR/Cas are nearly endless, and the next few years of development are sure to bring a lot of excitement and surprises.

References

The following links form a good set of references for more in depth reading; these form the bulk of my research prior to writing this guide.

-

Gizmodo, "Everything you need to know about CRISPR, the new tool"

-

CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes.

-

CRISPR/Cas9 and Targeted Genome Editing: A New Era in Molecular Biology

-

Biology StackExchange, "How does non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) work?"

-

The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems