I've previously written about a number of machine learning techniques. However, when you first encounter a machine learning task, what do you try? Though neural networks and support vector machines and deep learning are very interesting and might make for great writing topics, Occam's razor tells us that really, we should be trying the simplest things first.

The simplest technique in machine learning is probably something very intuitive, something most people wouldn't even categorize as machine learning: \(k\)-Nearest Neighbor classification. Using a neural network for a problem where \(k\)-nearest neighbors would suffice, just because neural networks are more powerful in general, seems analogous to the classic problem of premature optimization. In other words, worth avoiding.

A \(k\)-nearest neighbor classifier is incredibly easy to describe: if you have a labeled data set \(\{x_i\}\), and you want to classify some new item \(y\), find the \(k\) elements in your data set that are closest to \(y\), and then somehow average their labels to get the label of \(y\).

In order to implement this, all you really need to do is answer two questions:

- What is distance? Namely, if I have some \(x \in \{x_i\}\), how do I determine the distance from \(x\) to \(y\)?

- If I know that \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k\) are the \(k\) nearest neighbors of \(y\), how do I "average their labels"?

The answers to these questions depend greatly on exactly what you're dealing with. If you're dealing with textual data, then distance may be very hard to define; on the other hand, if you're dealing with points in a Cartesian coordinate system, we can immediately use our standard Euclidean distance as a distance metric. If your labels are real values (and your problem is a regression problem), then you can literally average them to get the label of \(y\); however, if your labels are classes, you may have to devise something more clever, such as letting the \(k\) neighbors vote on the label of \(y\).

Handwriting Recognition with k-Nearest Neighbors

Let's go ahead and implement \(k\)-nearest neighbors! Just like in the neural networks post, we'll use the MNIST handwritten digit database as a test set. You may be surprised at how well something as simple as \(k\)-nearest neighbors works on a dataset as complex as images of handwritten digits.

We'll start off with a generic class for doing \(k\)-nearest neighbors.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | |

You'll immediately be able to notice two things. First of all, unlike many other models, we don't have any preliminary computations to do! There is no training phase in a \(k\)-nearest neighbor predictor; once we have the data set, we can make predictions. Also, this is a non-parametric model - we don't have any structure imposed on the predictor by some fixed parameter list, but instead the predictions are coming straight from the data.

The second thing you'll notice - possibly while cringing - is that the implementation above is terribly inefficient. If you have \(N\) training points in your data set, computing the distances to each point will take \(O(N)\) time, and then getting the first \(k\) values by sorting the data set based on distance will take another \(O(N \lg N)\) time, so you'll spend $O(N N) $ time for each prediction you want to make.

This is definitely suboptimal. We can improve this to \(O(kN)\) without much difficulty, simply by mimicking the first few steps of selection sort:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | |

This is still pretty terrible - if we're predicting thousands of points and have a large training data set, this can become pretty slow. But let's ignore that for now, and actually get something running! (There are ways to improve this runtime, but \(O(kN)\) is the best we can do without some pretty serious and very cool trickery.)

Reading the MNIST Image Database

We're going to have to deal with the ugly details of MNIST now. I'm providing the code below, but there's not much interesting to talk about.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | |

Now that we have the binary data, we can try to parse it. The file format used is pretty simple. Both the image and label files start with a 32-bit integer magic number, to verify integrity of the file. The next 32 bits are an integer letting us know how many samples there are in the file. After those two values, the label file contains unsigned bytes for each label. The image file has two more metadata integers (both 32 bits) representing the number of rows and columns in the images, and then just contains unsigned bytes for each pixel. (The images are black and white.)

This is ugly, but let's go ahead and parse these files. (For the record, I'm getting this information and magic numbers from here.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 | |

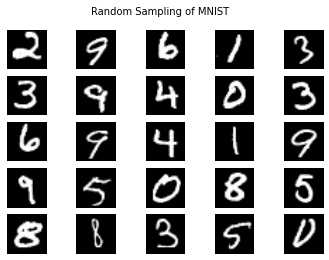

Alright, we finally have our data in usable form. Let's look at it, by the way!

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | |

Looking good! Note that the MNIST database defines "0" to be white and "255" to be black. This is the opposite of what normal pixel intensities represent, which is why it's being displayed as white on black. But this doesn't matter for our purposes, so we'll just leave it be.

Classifying Handwritten Digits

Looking good! Alright, now let's finally answer those questions from the beginning of this post.

How are we going to define distance? It turns out there's definitely more than one way to define the distance between two images, and choosing the best one is crucial to good performance both in terms of accuracy and speed. But first, let's start with the simplest distance possible: Euclidean distance.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

One down, one to go. How are we going to take a consensus from all the \(k\) neighbors? This one is easy - just let them vote. Take the majority vote as the right answer!

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | |

Alright, let's finally make our classifier and see how it does. We've done all the hard work, now just some boilerplate code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | |

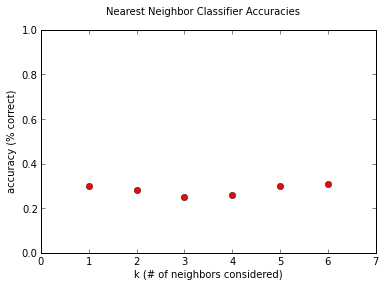

Note that we haven't really put any thought into what \(k\) should be. Is one a good value? What about ten? What about a hundred? The greater \(k\), the better our predictions, right?

The true answer is that we don't know. The right way to find out is through a method called cross validation, but right now we can just take a look at how it does for several different values of \(k\).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | |

Our classifier is way too slow to run the entire test set. Suppose we did want to run every image in of the ten thousand test images through the predictor. There are fifty thousand training images; so each prediction takes \(50000k\) image comparisons. We had values of \(k\) which summed to \(1 + 3 + 5 + 10 = 16\), so each prediction incurs 0.8 million image comparisons. Since we would have had ten thousand images, that would make for a total of eight billion image comparisons.

Suppose you had a 4 GHz CPU (I don't). And suppose that there was no overhead, and the only operations it had to do were the subtractions. Each image comparison incurs 28x28 operations, on the order of a thousand. That becomes a total of 8000 billion operations total, which, at 4 GHz, is slightly over half an hour. (I suspect this is about right, but we might be off by an order of magnitude. I wouldn't be surprised if it took four or five hours total.)

Evaluating Our Predictions

Let's see how we did. We can compute the accuracy by seeing what percentage each predictor got right.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | |

Surprisingly enough, it isn't terrible. Considering the chance of guessing randomly would be around 10%, our classifier is doing significantly better! But still, this is far from good, given the performance of neural networks in the previous post. It's interesting to note that the dependence on the value of \(k\) seems pretty weak, at least for the small values we're investigating. This is due to the pleasantly-named Curse of Dimensionality, which I might discuss sometime in the near future, as it's pretty much the reason that machine learning is Hard with a capital H.

There's a ton of stuff we could do to make this better. For our own convenience, we could start by parallelizing these operations, so we don't have to wait four hours for our results (if we have multiple CPUs). More interestingly, we could think of a better distance metric. For instance, we could use principal component analysis to project each image down to a lower-dimensional representation, and then use Euclidean distance in the lower dimensional space. We could also use a more intelligent neighbor-finding algorithm. These exist, but they aren't pretty, and have their own limitations to consider.

But those are for another blog post.